Paper Investments

By Karl Saffran, Urban Gateways Finance & Operations Associate

This blog was originally written for and published by the Americans for the Arts ARTSblog; see the original post here.

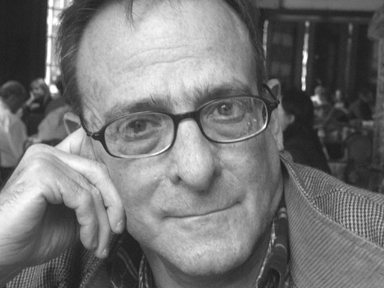

Last Friday, one of my favorite poets, Ted Greenwald, died after a long illness. I’ve met many great poets while working for poetry centered organizations, such as Woodland Pattern Book Center, a non-profit literary arts center in Milwaukee, but I never had a chance to meet Ted. Instead, as is usually the relationship between readers and writers, I knew him from his books.

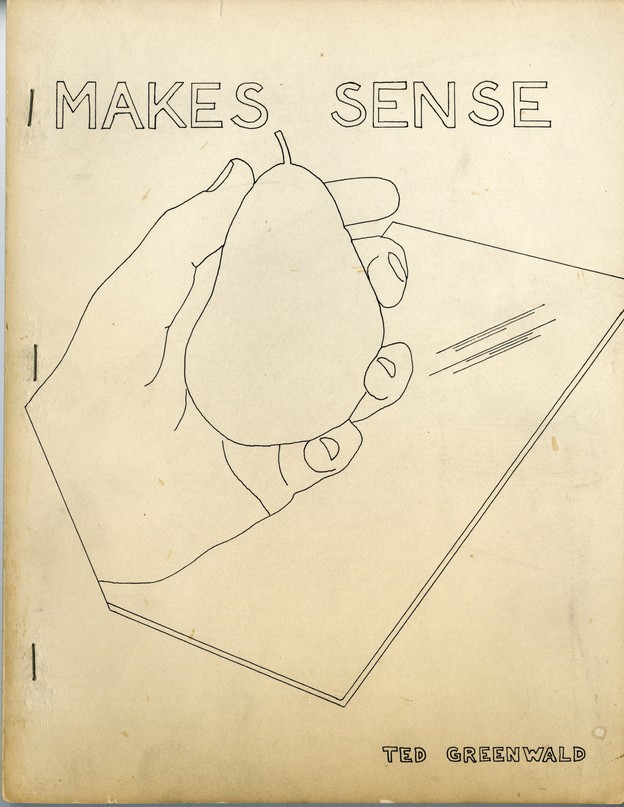

Over the past forty years, Ted Greenwald had at least thirty books of poetry published. Many of these books are chapbooks, published by small presses, often individuals, and printed (mimeographed, photocopied, letterpress, LaserJet, depending on the era) at home and assembled by hand. And while many chapbooks from these particular poets are now rare and expensive, they were originally made and sold cheaply, with the intention of quickly disseminating new poems to the hopefully eager masses.

This type of publishing exists, and indeed thrives, today. In many ways, it’s the perfect publishing fit for the many micro-communities that make up the larger world of poetry. (There aren’t many readers, so there’s no use printing too many copies, etc.) Levels of quality can vary remarkably, from poorly folded black and white covers to hand-stitched bindings and homemade paper, but it’s safe to say that no one is getting rich off these endeavors. Instead, most small presses dream of merely breaking even.

So why do it, when there’s no money and certainly no fame involved in producing small books of poetry? Most small press publishers do what they do simply because they feel there is writing that deserves to be read. A similar spirit extends beyond publishing, into the hosting of reading series in bars or apartments so that poets have a chance to share their words, creating websites to host poems and reviews, or creating non-profit organizations that find other ways to support poets. All of these activities take tremendous amounts of time and, in most cases, cost more money than they could ever hope to bring in.

So why do it, when there’s no money and certainly no fame involved in producing small books of poetry? Most small press publishers do what they do simply because they feel there is writing that deserves to be read. A similar spirit extends beyond publishing, into the hosting of reading series in bars or apartments so that poets have a chance to share their words, creating websites to host poems and reviews, or creating non-profit organizations that find other ways to support poets. All of these activities take tremendous amounts of time and, in most cases, cost more money than they could ever hope to bring in.

Far from being bad businesspeople, these editors, publishers, and curators are unsung investors in community. We rightfully spend much time and attention on both arts education and celebrating the work of established artists, but the period in between also requires care and nourishment. By investing in and supporting the work of emerging artists and writers, they create communities, locally and on a larger scale, that provide support to a bigger group of writers—a decent ROI.